Let’s say you’re in a position of leadership.

Maybe you lead a small team, a large organization, one part-time intern, a group of volunteers - maybe your position of leadership is formal, informal, explicit, or implicit.

Whatever your situations is, you have accepted a level of responsibility greater than those you’re working with.

And now it’s up to you to make sure that shit actually works.

It falls on you to make sure that projects are finished on time. That the pieces fit together and that no one murders each other along the way.

So, what should you do about this?

How do you get the people on your team to actually do all the big, medium, and small things that need to happen, at the right time, and in the right way?

Should you sit down, create a project plan along with a task list and timeline for each team member, and hold a meeting with each person to hand out their assignments?

This might make it difficult to make sure people are working together well, so maybe it would be better to create a unified “master plan”, and present it to the whole team team at once, so everyone understands how their part fits with the whole. You can then delegate each portion of the project.

Is this how it’s supposed to work? Something like that? The CEO is like supposed to tell everyone what to do? Leaders plan, non-leaders execute?

So, no.

Not anymore at least.

Now, depending on your background, this might seem like the most obvious thing in the world, maybe sort of interesting and a little counter-intuitive, or perhaps like down right heresy.

If this does seem obvious that the “master plan then delegate” model of leadership is broken - bear with me here, there’s some really interesting things that fall out of examining where this model breaks down.

And if this all seems ridiculous - definitely bear with me - I think you’ll really enjoy our discussion of former US Navy Captain David Marquet’s book Leadership is Language.

I’m The Boss - I’ll Do the Thinking, You Do the Doing

Isn’t that what leaders are supposed to do? Tell their teams what to do and make sure they get it done?

In Leadership is Language, David Marquet argues that this model of leadership no longer works, discusses why it can be really difficult to change, and presents six strategies for developing a more effective model of leadership.

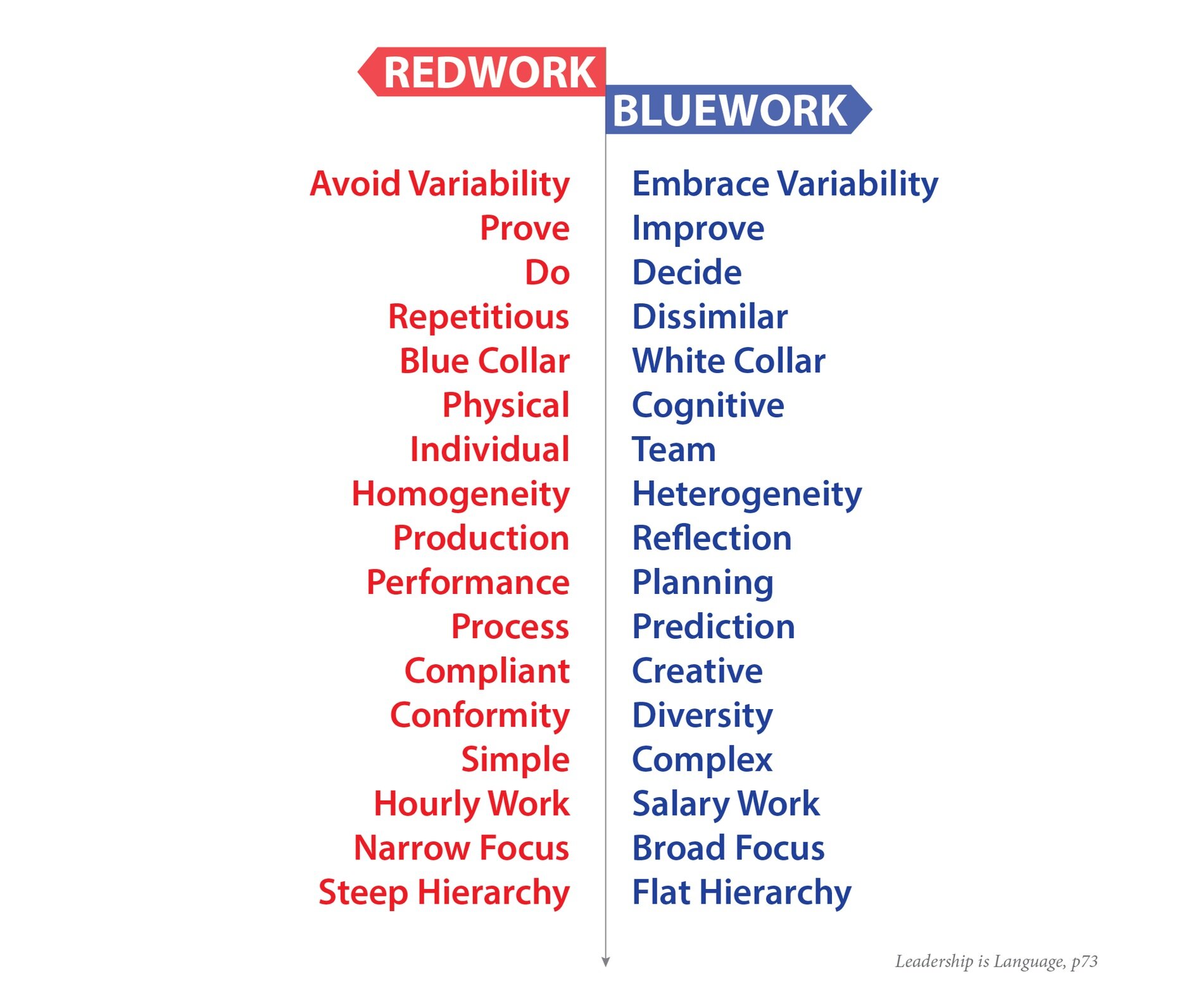

David starts with some nice definitions that really help clarify the central dilemma here. Notice that in our “master plan then delegate” model of leadership, the leader does the thinking/planning/decision-making work, and the team does the execution/doing work. David gives these types of work the names “bluework” and “redwork”, and posits that these two types of work require very different types of thinking and language:

Now, notice that in the “master plan then delegate” model of leadership, bluework is the work of one group of people (management/leadership), and redwork is the work of another distinct group. Marquet argues that this division is artificial and really only around because of the role it played in the industrial revolution:

“While bluework and redwork exist in every organization today, blue workers and red workers do not have to. However, as a result of the legacy of an artificial construct invented during the industrial revolution, we have cultural labels and uniforms to identify which group you are in: leader or a follower, salary worker or hourly worker, white hard hat, or blue hardhat, lab coat or overalls. We still want to make it clear which team you are on.”

Further, Marquet argues that this division is not only artificial in modern organizations - but also dangerous - it could jeopardize the organization’s very existence:

“Now, that is all changed. For organizations to survive, the doers must also be the deciders. We need the same people who used to view variability solely as the enemy to periodically view variability as an ally. We need the same people who used to have only a performance mindset to periodically have an improving mindset. ”

This is a strong assertion - basically that your organization will die if you try to run it this way.

So, what makes Marquet so confident about this?

Why does he believe this to be true?

What exactly is wrong with this model of leadership?

Stop Pretending You Have All the Answers

A big chunk of Marquet’s argument boils down to something like this:

The faster the world changes, the less leaders know.

Drawing on examples from the auto industry and elsewhere, Marquet argues that world is just changing too quickly now for the “master plan then delegate” strategy to work anymore - leaders just don’t and can’t have enough knowledge to do this effectively.

“Henry Ford revolutionized human mobility with the introduction the Model T in 1908…the idea was for leadership to come up with the One Optimal Way to mass-produce the One Optimal Design. The subsequent production run would then be continued for as long as possible. This approach reduced the redesigning, retooling, and retraining costs. It successfully produced cars so efficiently that even the people building the cars could afford to buy them. In 1908, this was a revolutionary idea.

…But the world was changing. Consumer spending power ballooned during the Roaring Twenties, driving the demand for cars with modern appointments and flashy looks. By this point, Alfred Sloan had been appointed president for General Motors Corporation. In addition to refining the assembly process, Sloan experimented with introducing annual updates to vehicles. Consumers strongly preferred more up-to-date models to the by-then tired look and feel of the Model T.

…Sales of the Model T peaked in 1923 with 2 million units sold. Then, in both 1924 and 1925, sales dropped, even his overall automobile sales continue to increase. The market has shifted. Finally acknowledging the problem Ford shut down as assembly line for six months - halting redwork – to retool. But it was too little too late. Ford’s pause gave GM the opportunity to catch up and then pass for it all together overtaking what was an unassailable lead.”

And of course, as Marquet points out - this rate of change has only increased since the 1920s.

A faster changing world means that the perception/viewpoint/understanding/information of blueworkers/leadership is getting worse. It takes time to figure out what’s really true about the world (e.g. will customers buy X, can we build solution Y leveraging open source technology Z), time that modern leaders simply don’t have if they want to move quickly enough to stay competitive.

Stop pretending you have all the answers.

Change is Hard Because We Still Have the Old Playbook

So, what’s the alternative?

Well, the main idea is pretty simple:

Empower your whole team to use their whole brains.

By making a master plan and delegating, effectively dividing your team into redworkers and blueworkers, you’re asking your redworkers to just shut off (or at least don’t bring to work!) the executive functioning parts of their brains - a big chunk of what makes us human!

Marquet uses a persona “Fred” to get across what it feels like to relegate your team to redwork:

“Better not to get to know them too well. What Fred does all day long is to deny his humanity in order to conform to his role. No wonder he gets home depleted.”

Now of course, platitudes like these are only going to get us so far.

Let’s say some of Marquet’s ideas seam pretty reasonable to you - what should you do about them?

What should you actually be doing instead of making a master plan and delegating tasks? Maybe send your team an email, something like: “Hey everyone, great news!I’ve decided to stop denying your humanity. You all get to do redwork and bluework now!”

All joking aside, making these changes can be really hard. The reason it’s hard, Marquet argues, is that it requires us to swim upstream against a series of assumptions, power dynamics, queues, behaviors, and very importantly language, left over from the Industrial Age.

Marquet breaks these down into 6 old “Industrial Age Plays” and suggests replacing them with 6 new plays, creating a new playbook for leaders.

Play 1: Connect, Not Conform

So you’re in a position of leadership, and you’ve decided that the “master plan and delegate” approach is maybe not the way to go.

But, how will your team actually know what to like, do? How will you get everyone working towards the same goal?

The first piece of the puzzle is is trust.

Trust your team.

Trust that your team both wants and is capable of doing the right thing for the organization. Do this even you don’t 100% believe it, because the act of trusting your team will change the way they behave.

“The Industrial Age play about trust needs to be turned on its head in two ways. First, we were programmed to make someone prove themself to be trustworthy before we trusted them. This naturally set up the case for judgment, not observation, and served to increase the power gradient. Now, leaders should trust first.

Second, trust does not mean you are always right. Trust simply means that your actions are being guided to support the best interest of the organization. This does not mean that your actions are always 100 percent in the best interest of the organization. This is important because without this underlying approach to trust, dissent equals distrust, and making a mistake once turns into “we can’t trust you”.

Assume Good Intent.

…trust people first because your trust in them will affect their behavior. They will work harder, stay longer, and unlock more discretionary effort when they feel trusted.

”

Now, if you find some of your team going down random tangents, getting off track, or not focusing on the important things - what should you do?

Well, there’s certainly a chance that one or more of these team members for whatever reason don’t have the best interest of the organization in mind or aren’t capable of doing what’s needed - but, what I’ve found in my experience more often then not, is that this really falls back on me as a leader.

I haven’t created a strong and vivid enough shared vision, and/or created the culture and space needed for the team to collaborate on and take ownership of the bluework/planning required to get us there. As David Marquet says “this is an issue of organization clarity”.

Trust your team.

Play 2: Collaborate, Not Coerce

Ok, so you trust your team. Now what? Trust alone does not replace master planning and delegation. The team isn’t magically going to work together on the important things just because you trust them.

So as you may have already gathered, the next idea here is really simple:

*Make the plan with your team. Collaborate. Do the bluework together.*

However, in practice, this can get messy. This is where Marquet’s argument about being stuck with old paradigms and language from the Industrial Age really starts to hit home for me.

“…this approach is far preferred to asking the question in a self affirming way - “are we all on board?” - and having the dissenting opinions lie dormant. Not only will the CEO and group be deprived of potentially critical information, but those dissenters, not having felt heard, will find other ways to sabotage the program.

”

Have you been in those meetings? Where the leader or someone with some level of power has decided that the organization is just going to do something their way?

How did it feel? Did you feel heard? Did it make you excited to move forward with the plan? Was the decision maker willing to be vulnerable, giving the rest of team permission to have a real conversation?

“Leaders say these things to assuage their conscience. When things go wrong, they can blame others for not speaking up despite the leaders encouragement to do so. But leadership is about making the lives of others easier, not blaming them. Leadership is about the hard work of taking responsibility for how our actions and words affect the lives of others.”

So, why do leaders do this? Why is making important decisions together not the default?

Many team cultures simply don’t allow them to do bluework together. Doing bluework demands an open, trusting, creative energy and environment. If you don’t cultivate this as a leader, your team will be stuck. They will be incapable of really collaborating on bluework, and you’ll be stuck as well - back with the master plan and delegate model of leadership.

Marquet shares lots of great strategies here for creating an environment where people will not feel judged for voicing their honest opinions - some very tactical such as having the team vote anonymously on important topics using “probability cards” - and then openly discussing without calling out individuals directly - along with more strategic approaches around reducing power gradients and setting the right tone as a leader through the language you use.

Play 3: Commit, Not Comply

So, you trust your team. You work hard to create an open and collaborative environment where your team can really make important decisions together.

Now, let’s say it’s time to make a big decision.

When will we ship our next release?

Should we do project X for client Z, even though it’s not exactly in line with our core focus?

Should we hire that new project lead?

How should we compensate the sales team?

What should our focus be for the next quarter?

You’ve created a great open culture where people feel comfortable expressing dissenting opinions.

Now, what if they do? Like actually express dissenting opinions? Now what?

You feel in your bones that your organization must do X, and 3/5ths of your team agrees. But you have two hold outs - they just don’t see things the same way - what should you do?

“NASA officials in the space shuttle Challenger disaster did the same thing, bluntly telling engineers they were wrong about the dangers of low temperature conditions during the launch. At one point a NASA official said, “take off your engineering hat and put on your management hat.”

When I hear a boss say things like “get everyone on board” or “build consensus,” that’s coercion. That’s trying to convince people “I am right, and you need to change your thinking.”

We don’t need anyone in the group to change their thinking. As long as the group supports whatever decision comes out of the meeting with their behavior, leaders are happy with individuals think differently from them. Otherwise they’re just in an echo chamber of their own ideas. There is power and resilience in diversity of ideas.

Do you believe that? I mean do you really believe that? If history is a guide, you think you’re special.

”

This passage really resonates with me. It’s not about changing people’s minds. And if you do try to directly change people’s minds, especially through coercion, you will be doing a great disservice to the culture and future creative potential of your team.

You don’t need consensus, you need commitment.

“Individuals make commitments. Groups do not. Commitment is personal; it comes from within.”

Play 4: Complete, Not Continue

But aren’t we back where we just started? How do we get the dissenters on our team to commit to a plan without forcing/coercing them to? Without just saying “tough shit, I’m the boss, the team has voted this way, deal with it”?

Well, first of all, we aren’t exactly back where we started. If you’ve really created an open environment, your team will feel more heard, especially your dissenters - and if you and the rest of the team are really listening - really interested in what they have to say and why they feel the way they do - then you have made progress - it will feel different.

And secondly, you, as a leader, will have dramatically better visibility into your teams thinking, and likely better visibility into the nature of reality.

But all that aside, it’s still tricky to move forward from a situation like this, where you’ve had an open conversation, and your team is split on how to proceed. This is a key area where I think Marquet’s Complete, Not Continue play is especially powerful.

The idea here is, whenever possible, take small bites, and then evaluate. Run experiments. When uncertainty is high and dissent is loud, run faster redwork cycles.

“Instead of handing down the mandate, though, announce an experiment: “Hey, let’s do this for a month and then we’ll talk about what we’ve learned and how we like it. If it turns out to be unhelpful, we can reverse the policy in a month.””

Instead of deciding once and continuing with redwork indefinitely, admit that no one in the room can predict the future, commit to take a small step and evaluate.

“…the next period of red work is the doing part of the learning cycle (make a prediction, then test the prediction by observing what happens, and reflect upon [your] observations with respect to our prediction), then it would be easier…to make that transition out of rumination and planning into action. ”

This approach will do two really valuable things to get buy-in from your dissenters:

Acknowledge that your dissenters may be right, there’s real uncertainty here.

Makes commitment much more palatable for your dissenters - it’s not forever.

Play 5: Control the Clock, Not Obey the Clock

So at this point you might be thinking something like - “Stephen, this all sounds great, but have you ever heard of this thing called…a deadline? When everything goes to shit and you just need the team to swing into you know, redwork or whatever, and get stuff done?”

So, yeah. I’m super guilty of this, and I do think that sometimes you just need to just act - deadlines and pressure can be really positive - there’s nothing like a lack of time to ruthlessly eliminate the unimportant.

The point here though is that like the other plays, there’s a layer to this dynamic that’s just left over from the Industrial Age, and no longer serves us or our teams.

An always ticking “Industrial age redwork production clock” applies pressure to keep marching forward, even if it’s on a path that makes less and less sense the further you go.

“As part of my tool kit to minimize delays, I would give speeches and advise my team on how much we had to do, how much I was counting on them, and how much others were relying on us. In other words I was deliberately making it hard for people to call time out. I was pre-emptying a pause. By preempt here, I mean taking action to prevent something else from happening in the future. In this case I made comments with the aim of keeping the team and redwork and making the barrier to exiting redwork higher.”

I’ve 100% done exactly this. Basically pretended that we had a “super open chill environment”, while applying deadline-induced pressure to the team through my energy and language.

Here’s some example language Marquet recommends for leaders in these situations that I found really humbling and compelling:

“You may have heard that this is an important milestone. That is true, but if we can’t get it done safely, I’ll recommend a postponement and I’ll be responsible for it.”

Play 6: Improve, Not Prove

“Here’s the rule with power gradients: the censoring of information is directly proportionate to the power gradient. Have a steep power gradients and employees will carefully censor the communication to the boss. They will edit out bad news, drafts and reword emails, and stay silent when the boss has suggested an idea, whether they think it is a good one or not. They will invoke the prove self.”

Ever does this?

Been writing an email, in a meeting, or on a call with your boss or someone more powerful than you - and felt that you had to prove yourself? Like really show that you knew what you were doing? Like you had everything figured out? Did you even maybe change your attitude and energy to be what you thought the more powerful person would want?

Marquet calls this the “prove self”. And again, I’m super guilty of this. Speaking directly from experience on both sides of the dynamic - it fucking sucks. For everyone involved.

Those with less power don’t bring their authentic selves to work and those with more power end up not knowing what’s actually going on. Think about how this impacts the organization as a whole - higher ups are blind and the rest of the team is disengaged.

These dynamics can become even more problematic as organizations shift to inviting more of the team to participate in bluework.

“Improvement – which comes from egoless scrutiny of past actions, and deep reflection thinking about what could be better– is the core purpose of bluework, which is meant to improve redwork. Bluework in isolation is useless. It’s relevant only to the extent that it makes redwork better: more efficient, more relevant, more resilient, more responsive. The improve play requires open-minded inquisitiveness and curiosity from everyone on the team.”

If your team is constantly in a prove mindset, it’s going to be really hard for them to objectively work through what could have been improved in the last redwork sprint. You can’t simultaneously prove to the boss that you’re “good” while sharing the 5 things that you and your collaborators did wrong over the last 2 weeks.

Again, Marquet points out that this really falls back on leadership. It’s up to those in power to create an environment where team members are comfortable to bring their full authentic selves, screw-ups and all - without crippling fear of judgment.

“Research from Amy Edmondson of the Harvard business school shows how difficult it is to activate the”get better” self to learn and improve in organizations that do not have a supporting culture. In a 2002 report, she states,”To take action in such situations involves learning behavior, including asking questions, seeking help, experimenting with unproven actions, or seeking feedback. Although these activities are associated with such desired outcomes such as innovation and performance, engaging in them carries a risk for the individual of being seen as ignorant, incompetent, perhaps just disruptive.””

Check Out The Book

If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend the book - Leadership is Language by L. David Marquet.

Stephen Welch

March 2021

Charlotte, NC